INTRODUCTION

For the last decade, the business model of “Free Wi-Fi” has been an open secret: it was a data extraction engine disguised as a service. The Captive Portal that splash page you see before connecting was designed not just to authenticate you, but to profile you.

With the operationalization of India’s Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023, and the subsequent Rules notified in late 2025, this ecosystem faces an existential overhaul. We are moving from a regime of “implied consent” to one of “verifiable, itemized, and revocable consent.”

Here is a detailed breakdown of how the Act dismantles the old architecture of Public Wi-Fi.

1. The New Digital Handshake: Section 5 & 6

In the pre-DPDP era, clicking “I Agree” on a Terms of Service (ToS) page was considered sufficient. The DPDP Act declares this invalid. The interaction between the user (Data Principal) and the Wi-Fi provider (Data Fiduciary) must now adhere to strict protocols.

1.1 The “Itemized Notice” Requirement (Section 5)

Before a single byte of data is exchanged, the Fiduciary must present a Notice. This cannot be a link to a 50-page legal document. It must be an “Itemized Notice” containing:

- Specific Data Points: E.g., “We are collecting your Mobile Number and MAC Address.”

- Specific Purpose: E.g., “To send an OTP for authentication as required by DoT regulations.”

- Rights: A clear declaration of your right to withdraw consent and approach the Data Protection Board of India.

The Multilingual Mandate: Crucially, this notice must be available in English and any of the 22 languages listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution. If a user in Chennai cannot read the notice in Tamil, the consent is technically void.

1.2 Affirmative Consent (Section 6)

Consent must be “free, specific, informed, unconditional, and unambiguous.”

- No Pre-ticked Boxes: A checkbox saying “Receive partner offers” cannot be pre-checked. The user must manually tap it.

- The “Conditionality” Ban: A provider cannot deny you Wi-Fi access just because you refused to share your email address (if the mobile number was sufficient for the legal requirement of authentication).

2. The Security Burden: Section 8(5)

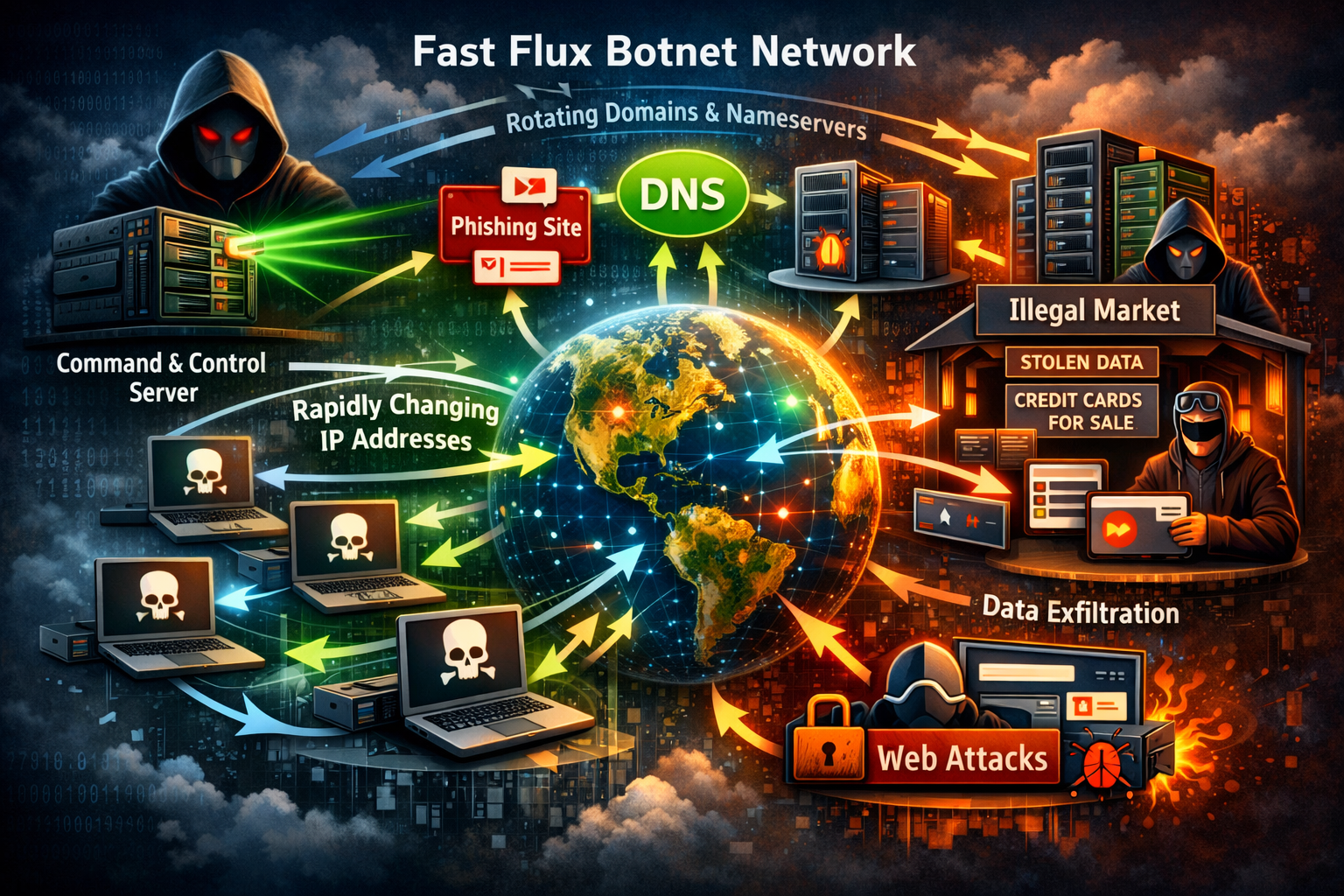

Public Wi-Fi networks have historically been security nightmares, often unencrypted or using weak WPA2 protocols with shared passwords. This negligence is now a massive financial liability.

- The Obligation: Section 8(5) mandates that the Data Fiduciary must implement “reasonable security safeguards” to prevent a personal data breach.

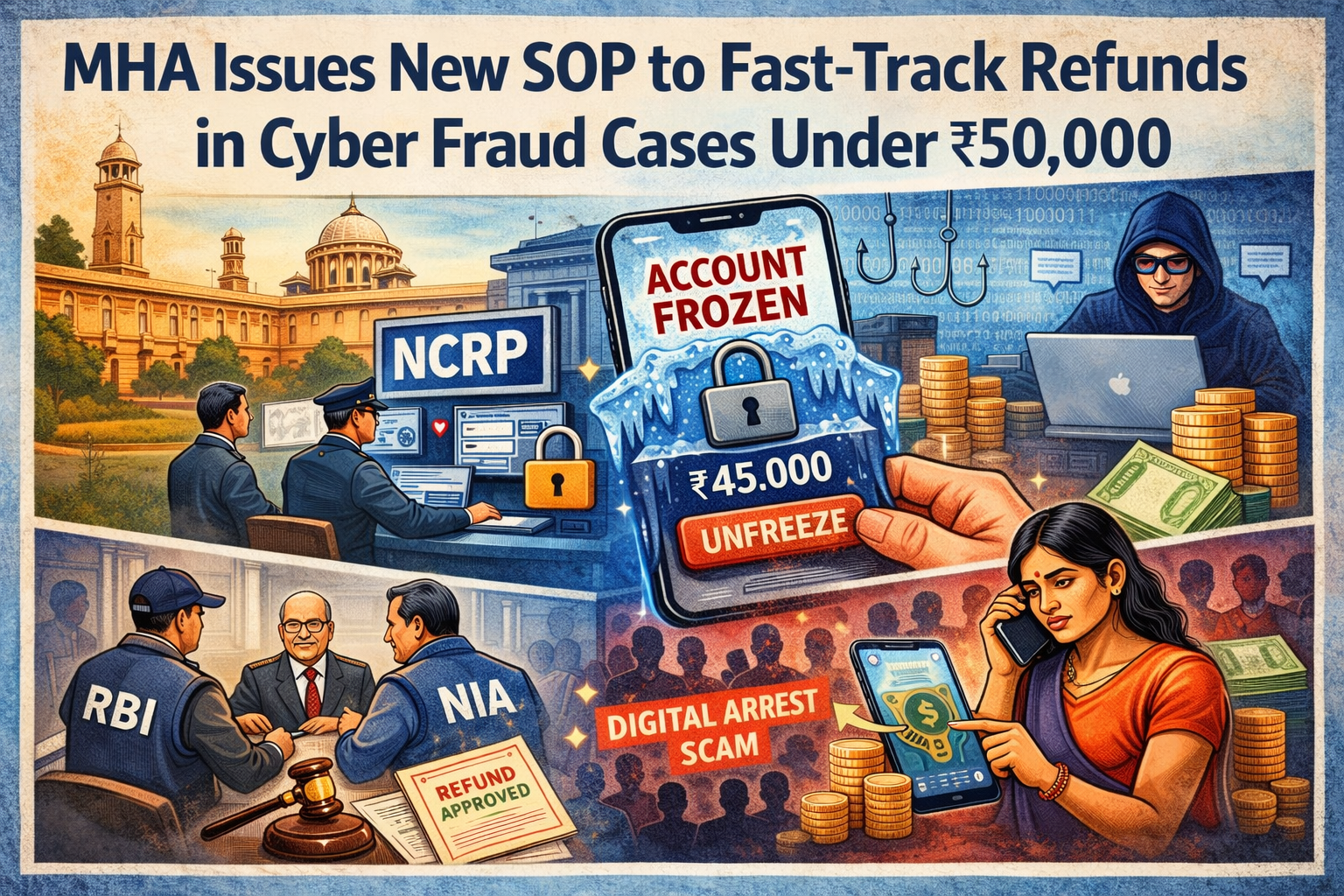

- The Stakes: If a hacker sets up a “Man-in-the-Middle” attack or breaches the cafe’s router logs to steal user phone numbers, the cafe (or the ISP managing the hotspot) can be fined up to ₹250 Crore.

This forces providers to move away from cheap, consumer-grade routers to enterprise-grade setups with proper network segmentation (keeping user data separate from the cafe’s POS system).

3. The “Erasure Paradox”: Section 8(7) vs. The IT Act

This is the most complex intersection of the new law.

Under Section 8(7) of the DPDP Act, a Data Fiduciary must erase personal data as soon as the “specified purpose” is served (i.e., when you disconnect from the Wi-Fi) or when you withdraw consent.

However, there is an exception: “…unless retention is necessary for compliance with any law.”

The Conflict:

- The DPDP Act says: Delete the data; the user has left the building.

- The DoT / IT Act says: ISPs and Public Wi-Fi providers must retain “Access Logs” (IP address, MAC address, time stamp, phone number) for a minimum period (often 1 year) to assist law enforcement in tracking cybercrime or terrorism.

The Compliance Solution:

The data cannot be deleted immediately, but it must be Quarantined.

- Commercial Use: The marketing team must delete the data immediately (0-day retention).

- Legal Use: The compliance team retains the data in a “Cold Storage” log for 1 year, accessible only if requested by law enforcement (Section 17 exemption).

4. Future-Proofing: The “Consent Manager”

The DPDP Act introduces a novel technical entity: the Consent Manager (Section 6(7)).

In the near future, you may not need to sign into every individual Wi-Fi network. Instead, you will have a “Consent Manager” app on your phone.

- How it works: Your app broadcasts your consent profile (“I agree to share my number for Wi-Fi access, but NO marketing”).

- The Handshake: The Wi-Fi router talks to your Consent Manager, verifies the permission, and logs you in automatically, maintaining a transparent audit trail of who has your data.

Summary Table: Old Way vs. DPDP Way

| Feature | Pre-DPDP Era | Post-DPDP Era |

| Login Screen | “I Accept Terms & Conditions” | Itemized Notice in 22+ Languages |

| Data Collection | Phone, Email, DOB, social media | Minimal Data (Phone/MAC only) |

| Marketing | Bundled with login | Separate, optional checkbox |

| Data Storage | Indefinite retention in CRM | Strict segregation: Marketing (Deleted) vs. Legal (Archived) |

| Breach Penalty | Minimal / Negligible | Up to ₹250 Crore |

Conclusion for Stakeholders

- For Users: You now have the power to demand why data is being taken. If a Wi-Fi portal asks for your Date of Birth, that is likely a violation of Data Minimization principles.

- For Business Owners: If you offer free Wi-Fi, you are a Data Fiduciary. Relying on a generic router setup is now a high-risk gamble. You need a Managed Service Provider (MSP) who understands the architecture of “Privacy by Design.”